(Image from WGEA)

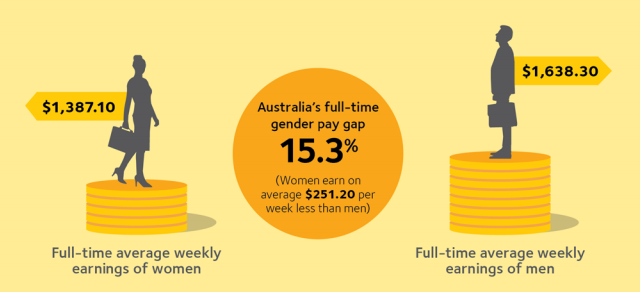

Gender inequality manifests itself in a range of ways including economic opportunities. Currently in Australia the national gender pay gap is 15.3%. There are several causes of the gender pay gap. They are rooted in gender inequality, one manifestation of which is discrimination and bias in hiring and pay decisions. The existence of male and female-dominated professions and industries that attract higher wages for men and lower for women is in itself rooted in rigid gender stereotypes and binaries. A nuanced analysis is required to understand why women are more likely on average to choose caring roles instead of careers in STEM, and this analysis cannot be done without acknowledging the impacts of gender stereotypes and prescribed roles and expectations on women. The gendered division of labour results in women’s disproportionate share of unpaid caring and domestic work and thus constitutes another cause of the gender pay gap. In Australia, mothers on average spend more than twice as many hours (8 hours and 33 minutes) each week looking after children aged under 15, compared to fathers (3 hours and 55 minutes).[3] Furthermore, Australian women account for 92 per cent of primary carers for children with disabilities, 70 per cent of primary carers for parents and 52 per cent of primary carers for partners.[4] Given that women are more engaged in domestic and care work, the lack of workplace flexibility to accommodate caring and other responsibilities, especially in senior roles, is another cause of the gender pay gap. Finally, women’s greater time out of the workforce impacts on career progression and opportunities. WGEA reports that the gender pay gap starts from the time women enter the workforce. The gender pay gap immensely impacts women’s lifetime economic security. The gender pay gap and subsequent lack of economic security contributes to the feminisation of poverty. In 2016, 13.8% of all women in Australia were living in poverty.[5] Women’s higher rate of poverty results from poorer employment opportunities, women’s over-representation in lower level positions, the gendered wage gap, women’s increased likelihood of performing unpaid caring roles and as a result women’s lower financial security in retirement.[6] In 2012, 38.7% of elderly single women compared to 33.8% of elderly single men were living in poverty.[7] The gender pay gap also results in women having less superannuation when they retire. The median super balance for a woman in the 55-64 age group was $80,000 compared to $150,000 for men. This represents a super gender gap of 47%.[8] As a result, as argued above, women are more likely to experience poverty in their retirement years and be far more reliant on the Age Pension.[9] Fear of lacking income especially in later life is a real and major concern for many women. In 2015 economicSecurity4Women produced a Lifelong Economic Wellbeing for Women in Australia report. It concluded that women of all ages are not confident that they will have sufficient funds to live with respect and dignity in later life. A number of respondents felt that they would have to defer retirement indefinitely. There is a need to improve financial literacy for women, enable pathways to education and future employment that do not discriminate on gender, and address the gender pay gap by creating equal opportunities for all. economicSecurity4Women https://www.security4women.org.au/ Workplace Gender Equality Agency https://www.wgea.gov.au/ [1] https://www.wgea.gov.au/addressing-pay-equity/what-gender-pay-gap [2] Ibid. [3] Australian Bureau of Statistics, 4125.0 – Gender Indicators, Australia, Jan 2012: Caring for Children (February 2012). [4] Australian Bureau of Statistics, 4153.0-How Australians Use Their Time, 2006 (February 2008). [5] This is higher than the poverty rate of Australian men, which was 12.8 per cent. See Australian Council of Social Service (2016) Poverty in Australia: 2016, p. 32, available at: http://www.acoss.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Poverty-in-Australia-2016.pdf [6] Australian Council of Social Service (2014) Poverty in Australia: 2014, p. 17, Available at http://www.acoss.org.au/images/uploads/ACOSS_Poverty_in_Australia_2014.pdf [7] Wilkins, R (2015), The Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey: Selected findings from Waves 1-12. Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, viewed 21 September 2016, available: https://www.melbourneinstitute.com/downloads/hilda/Stat_Report/statreport_2015.pdf [8] Australian Institute of Superannuation Trustees, Women in Super (2016) Women’s Super Summit 2016 [9] R Tanton, Y Vidyattama, J McNamara, Q Ngu Vu & A Harding, Old Single and Poor: Using Microsimulation and Microdata to Analyse Poverty and the Impact of Policy Change Among Older Australians (2008) p 15. Resources:

References cited: